E taku ipo translates as ‘my beloved’. I made this tobacco pouch in response to a call-out from Te Hikoi Musuem in Riverton/Aparima. This is where my tūpuna (ancestors), Pākehā and Ngāi Tahu, lived and died, and a place I have visited several times to connect to my lost kin.

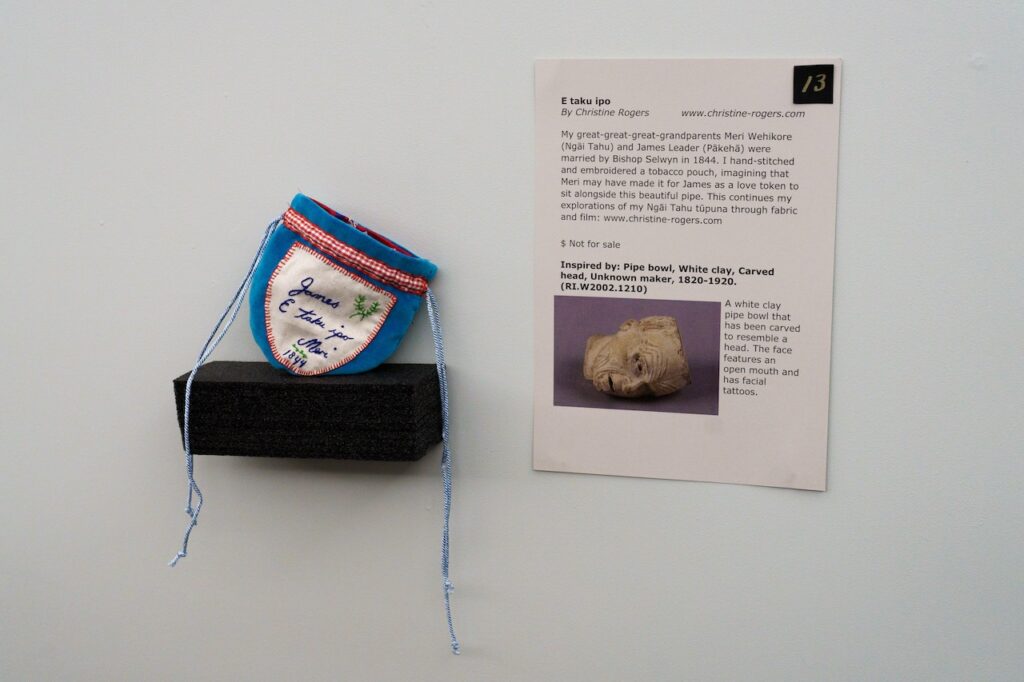

Framed as an art challenge, Te Hikoi asked us to make a work in response to an artifact in their extensive collection. I browsed through, finding several new and intriguing images of my Leader/Green/Arnett tūpuna, but what caught my attention was a small tobacco pipe bowl, pale clay, carved with the face of a toa (warrior) with moko (tattoos). No maker is listed and the pipe is dated between 1820 and 1920.

Such care had been taken in the carving of this beautiful pipe bowl. His face is expressive, his open mouth suggests speech or even sleep. When lit, perhaps smoke curls out of it, a humorous and unsettling doubling of the smoke curling out of the smoker’s mouth. I loved the skill and mystery of this domestic object.

I could imagine my great-great-great-grandfather James Leader being a pipe-smoker as sailors often were, and it was easy then to imagine his wife Meri Wehikore making him a tobacco pouch as a love token for their wedding.

I searched to find materials that were common in the mid-nineteenth century; blue velvet, a colourful red and blue satin lining as the Victorians were fond of bright colour, gingham ribbon and cord. I hand-stitched the pouch, but my skills are nothing like my fore-mothers, as you will know if you have ever looked closely at the perfect tiny stitching on Victorian clothing.

The embroidery came last; a simple message from Meri to her husband, who she would lose in the fast waters of Jacob’s River in 1852, 8 years after Bishop Selwyn had made formal what would have been a local marriage by local custom.

I was told by a distant relative that James drowned because he had lent his boat to Walter Mantell, the Commissioner for the Extinguishment of Native Claims, who was in Southland doing just that, trying to extinguish Ngāi Tahu claims. If this is true it is a terrible irony as Meri was Ngāi Tahu and their children too.

By stitching this imaginary memento I stitch my distant relatives into my life. In honouring what I hope was a marriage of love, I visit in my imagination that incredible time when strangers from different worlds met and began a new whakapapa (family tree) that stretches beyond me and into the future.