My hands have been busy, sometimes obeying the curving lines on the linen, other times ignoring them, stitching something new. I’ve been stitching a copy of a section of the Bayeux Tapestry, a 70-metre-long narrative embroidery stitched 900 years ago, to celebrate the victory of William the Duke of Normandy over King Harold II in 1066. But I’ve also added warriors of my own.

At the Battle of Hastings, William the Bastard became William the Conqueror, and the Normans became the rulers of England. The embroidery, commissioned not long after the battle, tells the story of the conquest from the point of view of the victors, although it was probably stitched in England by artisans.

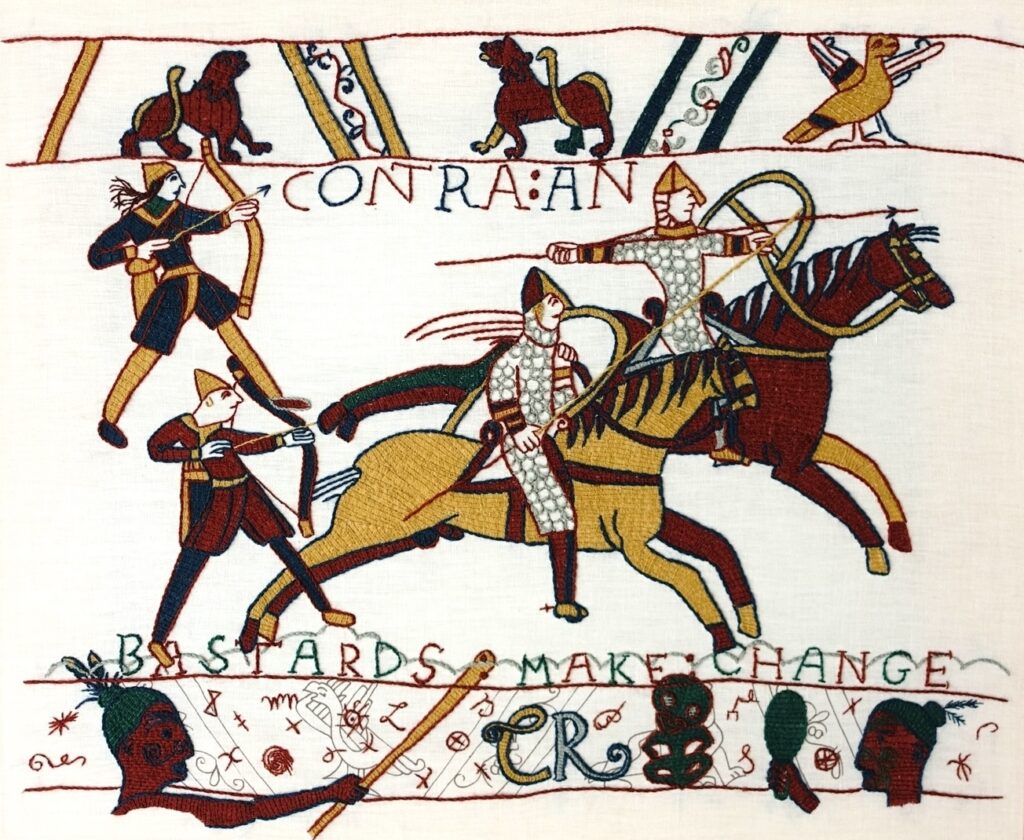

Several years ago, I travelled to Bayeux, France, to see the tapestry. The experience of viewing this ancient handmade cloth was unforgettable. It pulses with life. I was delighted to see nearby a craft shop selling exact replica scenes from it, the swatches of wool coloured to match the original tapestry colours. The piece I selected contains one word, which translates as ‘against’, and shows Norman horsemen and archers moving forward into the battle. Along the top and bottom are heraldic animals and motifs. Many of the lines are fabulously wonky. Originally they were no doubt straight, but the tapestry has weathered and miraculously survived 900 years, including two world wars.

My previous work honoured the stitching of Victorian women, now I was harking much further back, to when men and women earned their living as craftspeople. I brought the kit home, knowing that I would stitch it, but also change it, to tie it in with my own practice.

The stitches in the instructions were the same as the stitches used nine centuries ago, and it was slow work indeed. As I stitched, I contemplated. Being a bastard myself (illegitimate) I felt some pleasure in William’s victory and I thought about how his aggressive actions brought great change to England, some of it for the better. I decided to change two of the Norman warriors into women, a reaction to the overwhelming maleness of the original tapestry—there are only three women stitched among more than six hundred men.

My thoughts turned to peoples closer to my heart—the Māori, who, through a combination of clever politicking and bloody skirmishes, pressured the English colonials to draw up a treaty to protect Māori rights. These people were my ancestors, both Māori and Pākehā (New Zealand European). The Treaty of Waitangi, signed in 1840 by many rangatira (chiefs), is a flawed and fraught document but it has become a legal foundation for helping rectify the devastating effects of colonialism on Aotearoa New Zealand.

I decided to stitch two Māori warriors onto the cloth, over some of the Bayeux tapestry lines. I wanted to celebrate my kin as ‘bastards’ who made important change. One holds holds the patu (greenstone or pounamu club) and the other the taiaha, both weapons of warfare.

Around them are copies of rangatira’s signatures from the original Treaty document. These small and precious marks speak of a time of irrevocable change, when a rich oral culture was being transformed into a written one. Some are based on the moko (tattoos) that adorned their faces. I stitched a hei-tiki, a human figure often worn by women, and my initials. The work was now complete.

Māori adapted, they stepped forward into the modern while holding as tight as they could onto tradition. In this embroidery I too stitch tradition and change, honouring my fore-fathers who fought for the rights of our people, and honouring the skilled embroiderers of centuries past.

(greenstone).