It’s okay when you are lying down on the bunk, face inches from the bulkhead, listening to the waves slosh, slosh, slosh, and the relentless engine, feeling the slow roll.

And it’s okay on the back deck, behind the wheelhouse, breathing in an expanse of fresh cool blue sky, watching the light come up over the lumpy horizon of Rakiura (Stewart Island) while beneath you and all around you the boat rises and falls, rises and falls, rises and falls.

It’s the in-between that’s bad, getting from one to the other, sitting upright, head banging on the inside of the boat, struggling to swing your feet around, lurching out past the sleeping bodies strewn on the long window seats to the door outside, where the black dog and the white dog watch with plaintive eyes as I struggle to put on my shoes and not to heave. My body doesn’t want to be here, that much is for shore.

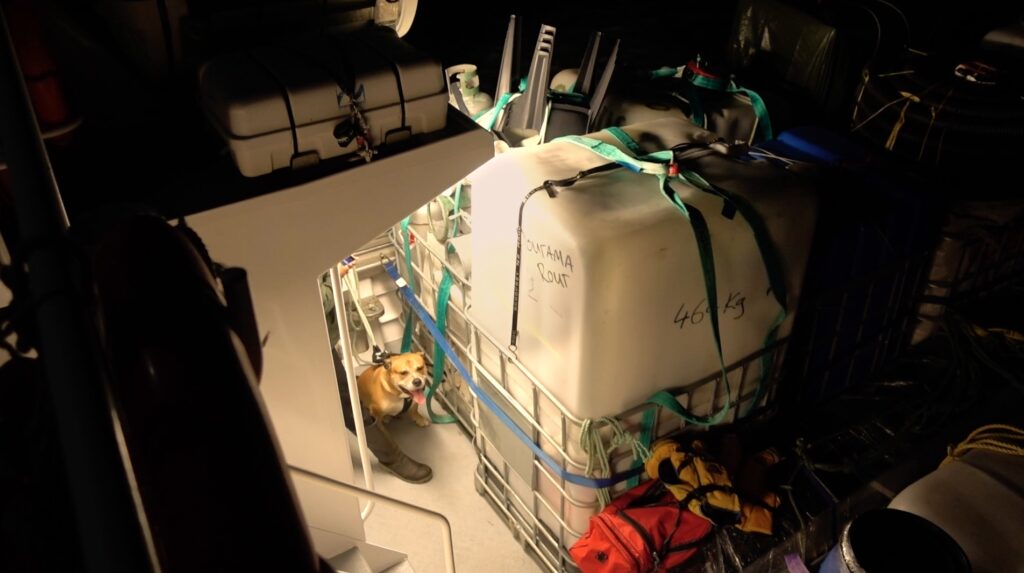

It’s a long way away from Bluff Harbour, this island I’ve come to see. It’s dawn and we’ve already been motoring since midnight. Now, in the crisp early morning, we pass many other islands, large and small, delivering people and supplies along the way, to their respective houses buried in the bush. People by dingy, motoring elegantly to the shore, waving back to us, calling farewell and wishes for a ‘good season’. Supplies by a helicopter that delivers a hook and line to lift each 400 kilogram plus load as delicately and accurately as an elephant lifts peanuts with its trunk.

We are in the south-western group of the Titi, or Muttonbird islands, and these people are here readying themselves to start the autumn titi harvest. Each of them is travelling to a house that belongs to family or to close friends. The house is on an island where their ancestors harvested. You need a permit from the Ngāi Tahu iwi (tribe) to even visit. It is strictly regulated, tied in with kin. It binds them together in a complex relationship with the past, with the land, and the birds. I am adopted. My Ngāi Tahu kin are probably here, not on this boat but on others, or in the faster and more expensive helicopters, but I don’t know them. This is why I can’t go, why I am watching and filming from the boat. I can’t travel with them, but my imagination can.

First, they will have to clean, and maybe fix up the house, as it has sat empty since the season last year. The rooms will fill with noise, with laughter, cooking smells. Small native birds will be scared away at first, then return, growing accustomed once again to people and their bluster. Then, when the season starts, each of them will gather with whānau (family) and friends and start pulling the fat grey down-covered chicks out of their burrows, killing them, plucking and then roasting or preserving them packed in salt to sell, exchange, or give away. These birds are prized kai (food) and this is a prized Ngāi Tahu cultural practice, a mahinga kai (food gathering) practice that has persisted here, at the bottom of the South Island, for centuries. Persisted despite colonization, loss of land, population decimation and the extensive intermarrying of Ngāi Tahu and Pākehā that is a feature of this part of the world.

But you wouldn’t guess it on the boat. The day is filled with excited talk and cups of instant coffee. The weather is furiously beautiful, the big dogs whine with ebbing restraint, and great Mollymawk birds swoop lazily to and fro behind the froth of the boat. No one seem filled with awe at the luck that this harvest persists. Flourishes. There’s none of the misty autumnal grain of an anthropologist’s film. Everything is as crisp and present as a shiny silver coin, a coin that is not mine, that I don’t get to spend.

But if I could go, could I do it? G tells me that she went as a little girl, and then again as a young woman, hoping to make some money for travel. She took the first bird out of its burrow and she was patting it, the down soft and warm. Her uncle told her if you don’t kill that bird right now you might as well just leave. She killed the bird and soon, she told me, she was used to it. I think about the bird and then I think about my small fat cat, how soft and warm she is when I rub my fingers on her stomach. I don’t think I could.

Like many places that you conjure in your imagination, the real thing is a little disappointing. It’s Poutama I have come to see, someone told me this is the place that some of my ancestors had muttonbirding rights to. It’s the most far south of this group of islands. It’s a small green-covered rock, under a mile square. Someone says it’s called Visitors Island because of the fancy houses with verandah’s. They don’t look fancy to me. I film it as we slowly motor past. The other side, towards the south, is rock and pounding sea. It’s too rough to land, and too dangerous to circumnavigate.

The boat turns, and we head away, chugging down the long stretch of the bottom of Rakiura, on and on through the beautiful day, the muttonbird islands disappearing behind us. Suddenly I’m tired and I want to go home.

I write this on the way home to Australia, keen to capture something of the feeling of the day. But it slips between the words. It might be there, in the footage; the never-ending sea, people in bright puffy jackets, dogs whining off-screen and the helicopter lifting its load into the blue sky, but it probably isn’t there either. Perhaps it is there in the quiet melancholy of the sunset as we leave Bluff and return to our own lives. Watch the short essay film I made of my journey here.