Recently my mother, who lives in Christchurch, was house-bound and she texted me to tell me she was “stitching and living very quietly.” At the very same time, on a summer holiday in Point Lonsdale, Australia, I too was stitching. My mother makes quilts. I’m embroidering a sampler.

In that moment we were powerfully connected. Connected, first, in a simple generational way, as a mother and daughter, both crafting. Connected, secondly, to untold millions of invisible women throughout time who have stitched to create useful, often beautiful, things for homes and clothing for their near and dear.

My mother, a skilled craftswoman, taught me. There was always something going on in our place; sewing, knitting, spinning, felt-making. Now she makes gorgeous quilts. She taught me how to knit and sew, and I continue to do both of these. I’ve also done macramé, hook rugs, cross-stitch, crochet, and now, embroidering.

These skills were like a background to my life, like knowing how to boil an egg. They seemed of little value. Is this because they were a ‘hobby’ (how I hate that word)? Is it because they are connected to the domestic and women’s skills? Women’s ‘work’. Of course, these three ideas are implicitly linked. My research and reading is making me revaluate my skills, to see them in a new light. To see them as something important, valuable, a transmitted knowledge.

When I was at school, in the 1970s and 1980s, we were taught sewing, cooking, woodwork and metal work. We all loved these classes. This kind of schooling was the long tail end of the kind of education that my ancestors would have had, where girls were taught stitching in school.

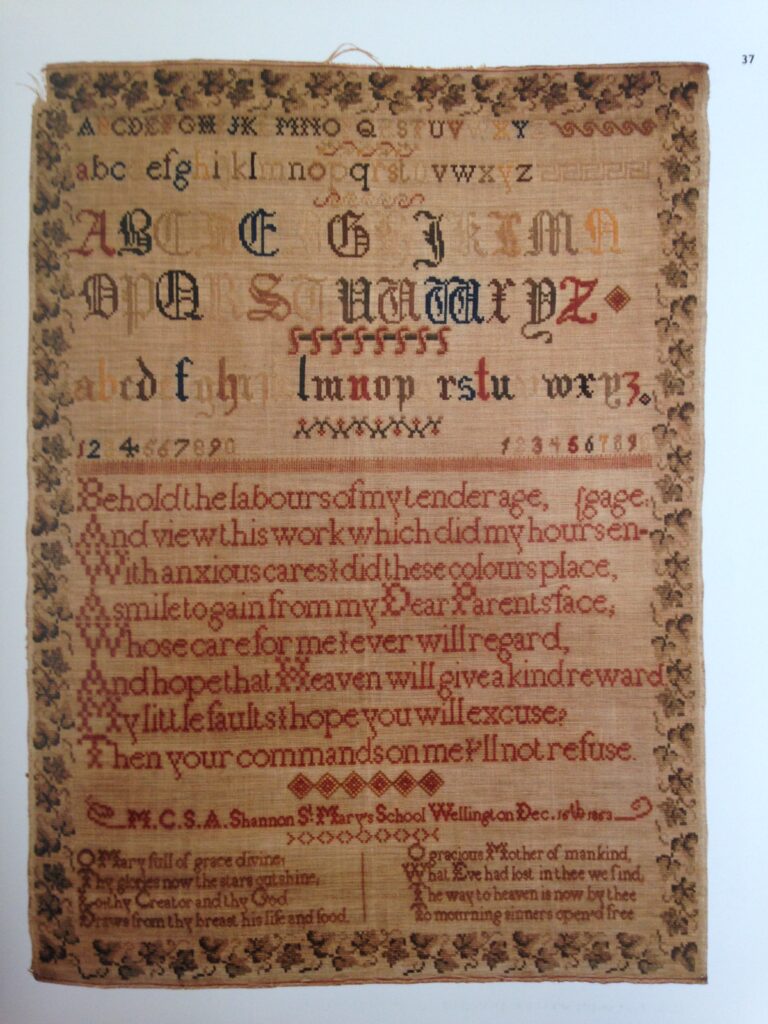

A sampler stitched by M C S A Shannon (1853),

from New Zealand’s Historic Samplers, Vivien Caughley, 2014.

Rozsika Parker in The Subversive Stitch writes that at the turn of the 20th century in English schools boys could win books as prizes for their study, whereas girls would just get to take home what they had been stitching, without having to pay for it. No books as prizes for girls, because girls were learning to be wives and mothers.

Still, these skills were vital to many households. Now, drowning in mass-produced clothing, it’s easy to forget that clothing used to be expensive, and unless you were rich, you would own only a few pieces and would extensively repair and remake that which you did own.

For working class women, stitching was the difference between eating and not. In Victorian England many worked alongside their young daughters in horrendous conditions, making fine fabrics and garments for the middle and upper classes. Middle-class women did not work, it was not ‘done’. So they stitched for other reasons; for creative satisfaction, for prestige, to stave off what Betty Frieden would call in 1963 “the problem that has no name” – a deep and pervasive unhappiness at being restricted to such a small life.

Middle-class Victorian girls embroidered samplers. The standard patterns of the time include alphabets and numbers, borders and motifs in various stitches, and often written bible verses or popular sentimental quotes about loving parents, obedient children, god’s greatness. Cut adrift from their original medieval purpose, to literally sample stitches seen in incredibly complex professional work, samplers became an activity designed to fill a girl’s time, a sign of her goodness and obedience, and an object to display her family’s middle-class status.

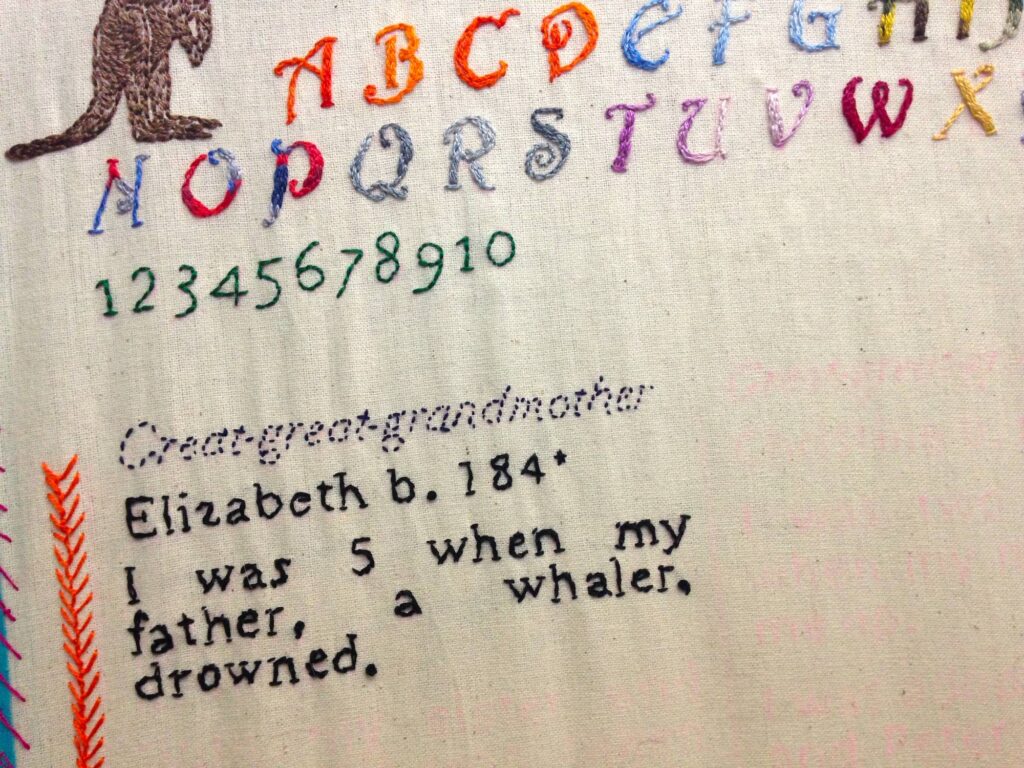

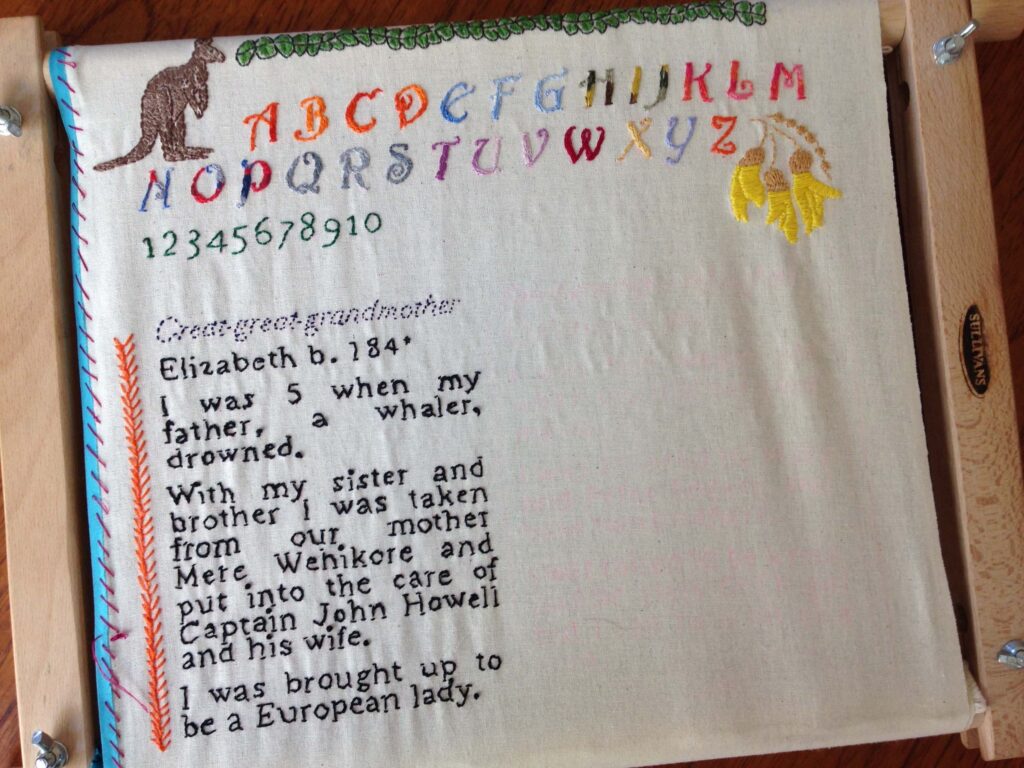

I’m making a sampler because of the lack of archival material on my great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Arnett née Leader. Elizabeth was mixed-blood, her mother Ngāi Tahu (Māori) and her father Pākehā (European), and she was born in the 1840s.

Her husband John, also Ngāi Tahu/Pākehā, has left many traces in the archives. He was an entrepreneur; a farmer, boat-builder, miner. John spoke at a Ngāi Tahu land rights hearing in 1879, describing how the failure of the government of the day to honour their pledges of schools, hospitals and money had drastically reduced his potential; “I am no scholar” he tells the government men, “If I’d been a scholar, I might’ve explained myself better.”

Elizabeth, the mother of his eight children, is missing from the archives. Even when she died, her death certificate and headstone are in the name of her second husband; Mrs John T Wesley. But I do know some things about her. Elizabeth’s father, a Pākehā whaler, drowned when she was 5 years old. Sometime after this, she and her siblings were taken from her Māori mother, Mere Wehikore, and raised by Captain John Howell, a local Pākehā businessman, and his wife.

So it’s likely that Elizabeth was brought up with Victorian cultural values and you can see this from the dress she wears in the photograph. It’s likely she attended school at some point. It’s likely that she would have been taught embroidery, either at home or at school, and stitched a sampler.

A few samplers still exist from this time, wonderful glimpses into young women’s lives. But I am adopted, so I don’t know if anything that Elizabeth made is still around. So I’m stitching a sampler myself, stitching Elizabeth’s, and my, story into a format that would have been deeply familiar to her. But I cannot help but break the suffocating conformity of Victorian samplers. No moralizing verses for me. I’m tapping into contemporary embroidery art practice that speaks to modern life.

Victorian women authors, throwing off the shackles of expected femininity, railed against the ‘bowed head’ of the embroider, confusing quiet and introspection with passivity. But it’s more complex than that. The writer Colette, watching her daughter embroider, was filled with apprehension; “She is silent when she sews, silent hours on end… She is silent, and she – why not write it down the word that frightens me – she is thinking.”

V & A Clothcutters Centre, London, 2018

Embroidering is a deeply introspective activity. It’s also incredibly calming. I find myself both intensely focused and free to think. You cannot be distracted or in hurry or the stitch will be in the wrong place, and ruin the thing. I have never before considered so closely the shape of letters—how curves are difficult in particular stitches, how straight lines are simple. There is much pleausere in the slow revealing of the pattern.

This activity makes us slow, gives us time to think, and deepens our connection with ourselves. Still, as ‘women’s work’, there remains a kind of cringe factor around embroidery. Imagine meeting me for the first time. I say I am a filmmaker—a moniker I have used for years—or I say I am an embroiderer. Which one makes you want to snigger? And there remain many gaps between what is seen as ‘fine’ art and craft. Still, gaps can be slowly stitched together. I am stitching away at the gap between Elizabeth and myself. I am sewing the past close. See more images of my sampler here.